3, Boulevard Bessières — Paris 75017

judysdeath@gmail.com

Visits by appointment

Theater of Cruelty

Hugo Bausch Belbachir in conversation with Chris Kraus

Hugo Bausch Belbachir: You moved to LA in the 1990s, after leaving New York.

Chris Kraus: ’95. I’ve been completely out of New York since the early 2000s when Sylvere left. For a while, when Sylvere was still teaching at Columbia I went back and forth until he moved here. That was pretty much it. I mean, it’s just so intense and difficult in New York. LA is very easy if you slip into it.

H.B.B: I felt like an alien, there. In a very Gothic way.

C.K: What were you thinking when you arrived?

H.B.B: I remember being there with my mother when I was around 10 or so, but as a completely different experience, of course. When I came back I arrived with a whole mythology and was immediately confronted with something much more brutal. I guess the tension of a linear space where people try to find something meaningful within it, but where it’s rather impossible to envision anything. Everything evaporates. I guess it also has to do with the fact that America has always denied social classes.

C.K: Oh, it’s so true.

H.B.B: And a taxi driver is a second-rate actor; daydreaming amid the highway. Symmetrically I kept on thinking about Julie Becker.

C.K: I have a friend, Ralph Coon, who’s writing her biography. He and Julie were very close. They were both addicts, although they never used together. But there was a lot of overlap in their experience, and they were friends. Ralph felt a lot of bad, a lot of guilt when Julie died, and he decided to write about her. He tracked down her parents, her brother, other family members, her ex-boyfriend, everyone.

H.B.B: Can you tell me more about them?

C.K: Her parents are really poor. Both were on welfare. Her mother is very sick now, with terminal cancer, she’s been living in Hawaii for quite a long time. Her father moved down to Baja California to a beach town not far from the border. He’s also living in extreme poverty, although he’s an artist and he’s still making work. Ralph visited him a few times down there.

H.B.B: I guess the work came to me within the transitory landscape that constitutes the city. This sort of constant in-between; people dying of fentanyl under tents in front of a Whole Fool. As if everything was short-lived; evanescent, fugitive. Or moving from one point to another and never getting lost, and never seeing anyone again.

C.K: Yes it’s completely disorienting. Although what you describe is fairly recent, going back to the pandemic. It was a little more orderly during Julie’s lifetime. Do you know who Giovanni Intra was?

H.B.B: I don’t.

C.K: Giovanni was a New Zealand artist who moved to LA in the late 1990s to do a critical theory degree at Art Center. He absolutely loved LA, and he did some incredible writing about urban and artistic ecologies here. He and Julie knew each other, did drugs together. Giovanni died of a heroin overdose in 2002, when he was just 34. We co-published a collection of his writings, Clinic of Phantasms at Semiotexte last year with a New Zealand press, Bouncy Castle.

H.B.B: How did you meet Becker?

C.K: I was doing studio visits at CalArts in the late 1990s when she was a student there. We just clicked, exchanged information and started hanging out. Although even in our friendship, talking about the work was always a big part of how we spent our time.

H.B.B: Can you describe her studio?

C.K: There was the one on Morton Street, which was underneath an old Craftsman-style bungalow near Elysian Park. She started making very large pieces while she was there. The house had a scary, dark grungey basement, actually more like a crawl space, that she used as a studio. But the house I think was foreclosed, owned by a bank, and eventually they sold it and she had to move. By the early 2000s she was living in the storefront studio on Berkeley and Sunset. Which was very urban, very NYC by LA standards – an ugly traffic snarled-corner with gas stations, auto parts and convenience stores. This was before LA became impossibly gentrified and polarised … but even back then, it was one of the ugliest locations I’d ever seen in LA. The storefront was mostly a studio – she just carved out a little living space in the back with a DITY kitchen, a shower and toilet. Like an old-fashioned NYC raw loft. Julie lived under those conditions for a long time. Around the time of the move, she’d started having more difficulties, lost her gallery representation and turned to drawing because she didn’t have the budget to make large-scale works at that time.

H.B.B: Did she write?

C.K: No, not so much. Not that I know of. She made videos.

H.B.B: Can you tell me about these days in LA, in the mid-1990s?

C.K: It was wide open. Nobody wanted it. The book we published recently with Semiotexte, Reynaldo Rivera, gives a really strong sense of that time. Rey took photos of Echo Park house parties and Latino drag/trans bars during the late 1980s and 90s. He didn’t have an art career per se, but he kept taking pictures. In the book, he and Vaginal Davis reminisce about those earlier days in LA. Rey has a profound sense of the city’s shifting identity, its amnesia, the erasing of Latino culture. He’s a great writer as well. For me, coming from NYC in the mid-90s, LA seemed thrilling because there was no competition. I’ve never liked competition. In LA at that time, it seemed like you could pretty much do anything, because nobody cared. The stakes were that low. And I think that kind of atmosphere is conducive to making art.

H.B.B: When did this shift?

C.K: Instantly. It started changing already, um – when did I write the Tiny Creatures essay? Around 2008? Everyone involved with that gallery was already aware of it then.

H.B.B: Wait, I need to close that window. It’s raining again.

C.K: Yeah, no problem.

H.B.B: Anyways. We also met through this film, yours,‘How To Shoot a Crime’, co-directed with Sylvère. How about those times, in New York?

C.K: New York was amazing, very similar to LA in the 90s, a place nobody wanted. I mean, of course it was always more competitive than LA but there were still some unsettled, mysterious places. But it being NYC, even amongst that legendary bohemian poverty and squalor, people were very aware of who went to which school, and of advancing themselves and their artistic careers. That didn’t happen overnight, NY was like that as long as I can remember.

H.B.B: I’ve always been fascinated with how labor, as a concept, is infused in America. Especially in New York. A constant horror.

C.K: Right; a horror.

H.B.B: You’ve been going back and forth more frequently to Mexico, too.

C.K: I like going to Mexico – I’ve been going there to write since 2004, and over the years I’ve developed friendships with other artists and writers in Tijuana and Mexicali. It’s nice to have at least a big toe in that world – it’s a reprieve from America. The people I know in those border cities could definitely have had lives and careers in LA, but they chose to stay there, which is a very interesting thing. You know? It’s like that early 20th century moment when generations of people decided to remain in New Zealand or Norway or even Chicago and make their work there. A widening of things, outside the center. Border culture on both sides of the US/Mexican border is really interesting – very street and vernacular and attuned to the realities of the globalized hyper-capitalism.

H.B.B: Do you apprehend writing differently in Mexico, or whenever you find yourself outside of the US?

C.K: I think I just write the way I’m going to write. I think about it for a long time, and then sit down to do it. But leaving the US is always such a relief. And then, I’ve never been good about writing at home. I’m talking to you from my office, I can do everything here except work on a book. If I’m writing a book, I need to enter a bubble, maintain one foot in that world. I think a lot of writers feel that.

H.B.B: Escaping, or looking for a context that goes against — creates a tension, let’s say — within the process of writing?

C.K: The book has to be the most interesting thing in your life in order to write it – the point that’s most alive. And I’ve found that hard to maintain in real daily life. Having very poor boundaries. Since I can’t seem to maintain them, I just run away.

H.B.B: Is it the same when it comes to writing criticism?

C.K: Nah. That I can do anywhere.

H.B.B: Do you still write criticism?

C.K: Occasionally, if it’s an artist I like and I want to engage with the work, I’ll do it. But it’s definitely less interesting to me now than writing fiction.

H.B.B: I remember you saying that it took you a while to know how to apprehend forms of contemporary art. I mean contemporary works. That you felt sort of intimidated; keeping a form of distance.

C.K: And now I enjoy it.

H.B.B: What are you working on, right now?

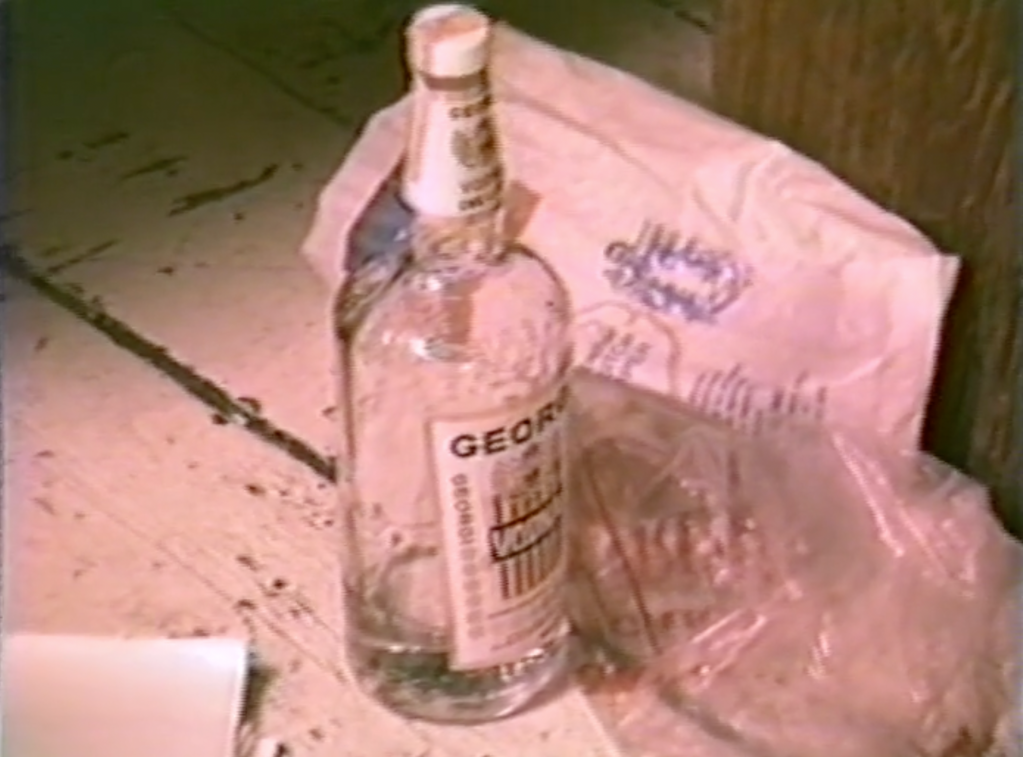

C.K: The novel I recently finished continues on, in a way, from Summer of Hate. The Catt and Paul characters find themselves in northern Minnesota – he’s gone back to school in Addiction Studies at Hazelden/Betty Ford, she’s gone with him to work on a book – and they end up buying a cabin together up north. Later, he relapses and moves up there full-time, working in social services by day, getting high nights and weekends. The book follows that struggle, and then shifts to a story I read in the local paper about three teenagers who kidnapped and shot an acquaintance – all high on meth. I started to do a lot of research, visiting them in prison and getting to know their families and friends, pretty much everyone in that world. It was actually the third violent methamphetamine murder in this tiny location during their teenaged years.

H.B.B: A case study.

C.K: Yeah. The up north cabin is all towering pines, loons, moose and bear – but 20 miles away in the town, there’s this rust-belt culture that supposedly asserted itself via Trump and MAGA. The kids really have nothing … it’s multi-generational poverty and addiction, they’re Reagan’s spawn – their world the consequence of complete indifference, deindustrialization, contempt. Researching the book, I immersed myself in the culture of those kids.

H.B.B: Are you still in contact with them?

C.K: I’ve become real friends with the accomplice. We’re in touch a few times a month.

H.B.B: How old are they?

C.K: At the time of the crime, the couple – a boy and a girl – were 18 and 17. The accomplice, my friend, was 19 and he’d just moved up there.

H.B.B: Where did the murder took place?

C.K: Hibbing, Minnesota. Birthplace of Bob Dylan. Did you know that? Well, not exactly his birthplace, but where he went to high school.

H.B.B (laughs): I didn’t.

C.K: Yeah, I think that’s funny too. And there’s a Bob Dylan Museum in the cellar of the public library. But the town now is just so fucked up.

H.B.B: In the middle of nowhere.

C.K: I’ve always been drawn to wild, remote, forgotten northern places. I loved it there.

H.B.B: Talking about the book brings me back to ‘How To Shoot a Crime’. I mean; case studying. Everything that is transactional; drugs — selling, buying —, sex — a worker, a client —, committing a crime.

C.K: You’re right. I thought about that film from time to time. Sylvere saw crime as a means of marking time and imposing one’s own identity upon an otherwise indifferent, anonymous city. In a huge megapolis everything’s always in motion, a perpetual flow, nothing sticks. But the crime stops time and motion: suddenly, an interstation space is transformed into a ‘crime scene’ and all this attention is paid to reconstructing events. Which is really interesting. I mean, the data is always there – pretty much anything can be reconstructed – but it’s very rare that someone will invest all that attention. I used a lot of police documents in this research. They’re very precise, in terms of chronology – but of course they ignore what to me is most interesting – the gestures, the conversations, how things looked and felt.

H.B.B: The contextual potential of details. Like writing poetry.

C.K: The crime does that, yes. It stops time. Traumatized all of his life by his childhood experience in Occupied France, Sylvere never felt things at first hand. So stopping time was incredibly compelling to him.

H.B.B: There’s this moment in ‘Video Green’ that I love. The one in which you mention Terrence Sellars and Mademoiselle Victoire; ‘Barely conscious that they are parading within an environment, and as such, they are emanating everything important of that environment. They’re emanating anxiety, longing, and fear.’

C.K: It’s touching to watch that, now that Terence is no longer with us. There’s a part of the film where Sylvere asks her Why do you have to be right all the time? And she says: Twenty years from now, there’ll just be this video of me at 32, talking. To her, time really mattered. I didn’t know Terence well, but I know that she eventually shut down her BDSM dungeon and moved out to New Mexico, to a high-desert town that for some reason attracted a bunch of 1970s Soho minimalists. It was a whole little enclave. She moved out there, and then trained as a nurse.

H.B.B: That makes sense; from dominatrix to nurse.

C.K: Yes.

H.B.B: She’s fascinating, in the movie.

C.K: She wrote a book, The Correct Sadist, have you ever seen it? She and Kathy knew each other. Kathy Acker.

Chris Kraus (b. 1955) is a Los Angeles–based filmmaker, writer, art critic, and editor whose novels include ‘I Love Dick’ (1997), ‘Aliens & Anorexia’ (2000), ‘Torpor’ (2006), ‘Summer of Hate’ (2012), and the forthcoming ‘The Four Spent the Day Together. Her literary biography of the writer Kathy Acker, ‘After Kathy Acker,’ was published in 2017 followed by the essay and story collection ‘Social Practices’ (2018). Kraus’ other collections of essays on art include ‘Video Green: Los Angeles Art and the Triumph of Nothingness’ (2004), and ‘Where Art Belongs’ (2011). Alongside Managing Editor Hedi El Kholti, Kraus is a co-editor of the publishing house Semiotext(e). She has written countless reviews, essays, and stories for publications such as Artforum, Art in America, Modern Painters, Afterall, The New Yorker, The New York Times Literary Supplement, The Paris Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Bookforum, and Texte zur Kunst. Kraus taught creative writing and art writing at The European Graduate School/EGS for ten years and has been a Visiting Professor at UC San Diego and Writer-in-Residence at the Art Center College of Design.

This interview was organized on the occasion of Chris Kraus’ inclusion in ‘The Ceremony’, Judy’s Death inaugural exhibition.

The Ceremony

Samuel Jeffery, Chris Kraus, Philipp Simon

February 10 — April 15, 2024

The Ceremony is the eponymous title of a film by Claude Chabrol, from 1995. I mainly liked the object; a rectangular cassette, a title in yellow, the faces of Sandrine Bonnaire and Isabelle Huppert looking in different directions, on a dark background. For a long time, it was simply a cassette. A box. The film is based on L’Analphabète. A book by Ruth Rendell. A Judgment in Stone in English. It’s the story of a bourgeois family who hires a housemaid. She’s illiterate, obedient, polite, punctual. We imagine that she had a hard life; she’s poor, little talker, unimpressed by this vain, intellectual family. In the film it’s the same. Then she develops a friendship with a girl in town, who is relatively vulgar. It’s a character I really like. She takes the story elsewhere. She pushes it to crime.